On Christoffel Symbols

You may have never heard of them before, but the Christoffel symbols are fundamental in tensor calculus and generally important whenever one works with an abstract surface or coordinate system. Let's begin with an easy example of where they show up.

Why Physicists Should Learn About Christoffel Symbols

Introduction

If you've studied general relativity or differential geometry, you've likely encountered the Christoffel symbols (also called connection coefficients). At first glance, they might seem like an obscure mathematical tool, but they play a fundamental role in understanding curvature, parallel transport, and the equations of motion in curved spacetime.

For physicists, mastering Christoffel symbols is essential not just for general relativity but also for continuum mechanics, gauge theories, and even advanced fluid dynamics. In this post, we’ll explore:

What Christoffel symbols are

How they arise in physics

How to compute them

Why they are indispensable in general relativity and beyond

By the end, you’ll see why every physicist should have a solid grasp of these geometric objects.

1. What Are Christoffel Symbols?

Christoffel symbols are not tensors—they don’t transform covariantly under coordinate changes—but they help define the covariant derivative, which allows us to differentiate vectors (and tensors) properly in curved spaces.

In flat Cartesian coordinates, taking derivatives is straightforward because the basis vectors don’t change from point to point. But in curved spaces (or even non-Cartesian coordinates like polar coordinates), basis vectors do change, and Christoffel symbols account for this variation.

Mathematical Definition

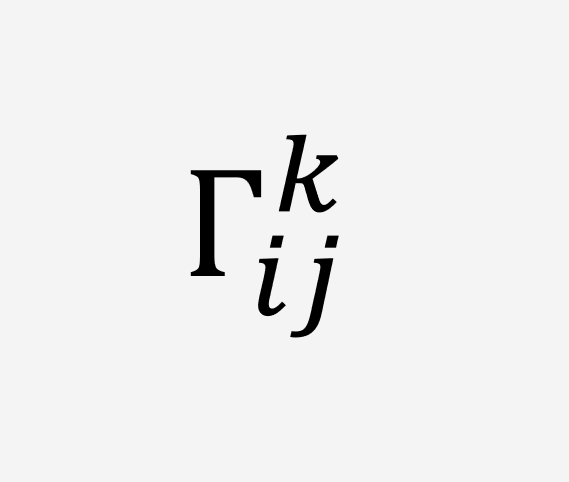

Given a metric tensor , the Christoffel symbols (of the second kind) are defined as:

Here, is the inverse metric, and denotes partial derivatives.

2. Where Do Christoffel Symbols Appear in Physics?

A. General Relativity (Geodesic Equation)

In Einstein’s theory of general relativity, particles in free-fall follow geodesics, the "straightest possible" paths in curved spacetime. The geodesic equation is:

Here, is proper time, and the Christoffel symbols encode how spacetime curvature affects motion.

B. Covariant Derivatives

In flat space, the derivative of a vector is simply . But in curved space, we must account for how the basis vectors change, leading to the covariant derivative:

Without Christoffel symbols, we couldn’t properly define concepts like parallel transport or curvature.

C. Continuum Mechanics and Fluid Dynamics

In continuum mechanics, Christoffel-like terms appear when working in curvilinear coordinates (e.g., cylindrical or spherical). Even in classical physics, accounting for coordinate-induced "fictitious forces" (like the Coriolis force) involves similar mathematics.

3. How to Compute Christoffel Symbols

Let’s work through an example: computing the Christoffel symbols for the 2D polar metric.

Step 1: Write the Metric

In polar coordinates , the line element is:

So the metric and its inverse are:

Step 2: Apply the Christoffel Formula

The non-zero partial derivatives of the metric are:

All other derivatives vanish. Plugging into the Christoffel formula:

:

Only contributes (since ):

:

All other Christoffel symbols are zero.

Interpretation

tells us that moving along introduces an "inward" curvature effect.

shows how angular velocity changes with radius.

4. Why Are Christoffel Symbols Important?

A. They Encode Curvature

While Christoffel symbols themselves are not tensors, they help compute the Riemann curvature tensor:

This tensor is fundamental in general relativity, describing tidal forces and spacetime curvature.

B. They Generalize Newtonian Gravity

In the weak-field limit, general relativity reduces to Newtonian gravity, and the Christoffel symbol (where is a spatial index) relates to the gravitational potential :

This bridges Einstein’s theory with classical gravity.

C. They Are Essential for Numerical Relativity

When simulating black hole mergers or neutron stars, numerical relativists must solve Einstein’s equations, which involve Christoffel symbols in the 3+1 decomposition of spacetime.

5. Common Pitfalls and Misconceptions

Christoffel symbols are not tensors – They transform inhomogeneously under coordinate changes.

They vanish in locally inertial frames – By the equivalence principle, we can always choose coordinates where at a point.

They depend on the metric – Different metrics (e.g., Schwarzschild, FLRW) give different Christoffel structures.

Conclusion

Christoffel symbols are the "glue" that connects calculus and geometry in physics. Whether you’re studying:

General relativity (geodesics, curvature),

Continuum mechanics (stress in curved materials),

Gauge theories (non-Abelian connections),

understanding Christoffel symbols is crucial. They may seem abstract at first, but with practice, they become an indispensable tool in a physicist’s toolkit.

Further Reading

Gravitation by Misner, Thorne, and Wheeler

Spacetime and Geometry by Sean Carroll

The Geometry of Physics by Theodore Frankel